Manhattan breathes.

Not in the metaphorical way people talk about cities having a “pulse” or “rhythm.” I mean it literally exhales steam from underground vents that curl around your ankles on winter mornings like phantom cats. It inhales masses of people through subway grates and exhales them elsewhere, transformed somehow by the journey beneath the concrete skin of the island.

I’ve been watching this breathing for three months since I moved here from Baltimore. Three months since I packed my life into a Toyota Corolla, hugged my mother tight in the driveway, and told her I’d be fine. Three months since I arrived in New York with a nursing license, one suitcase, and faith stitched into the lining of my coat.

My hands remember the weight of a human heart before my mind fully wakes each morning.

Cardiac is my home—where I’ve memorized the precise cadence of bypass machines and can distinguish between twenty different suture needles by touch alone. But today, I’m floating to orthopedics again. “Critical staffing,” the charge nurse had texted at 4 AM, desperation leaking through the blue light of my phone.

Sixteen hours later, my shoulders burn from holding retractors steady during a spinal fusion, my scrubs bear the invisible map of other people’s salvation, and somewhere beneath the bone-deep exhaustion, there’s a peculiar euphoria. The hospital swallows time differently than the world outside—minutes stretch into eternities when a patient’s pressure drops, yet entire shifts vanish in the windowless glow of operating suites where the only seasons measured are in the changing rotations of residents.

I love my job.

We are a tribe of strange people—nurses, surgical techs, anesthesiologists, residents—bonded by adrenaline and gallows humor. My badge says Oyinyechi Okonkwo, BSN, RN, CNOR, but most days they just call me “O.” Easier on the tongue, they say.

Less risk of butchering the vowels.

The OR smells the same at 3 AM as it does at noon—antiseptic with undertones of electrocautery, iodine, and the metallic scent of blood that somehow permeates through double-layered masks. I assist Dr. Archana with a triple bypass, anticipating her needs before she voices them.

I hand her the Metzenbaum scissors, then the forceps, then the silk suture, because I’ve learned to read the slight shifts in her posture, the microscopic changes in the tension around her eyes. We work in near silence, a choreography more intimate than any dance I’ve shared with a lover.

“Beautiful work today, O,” she says afterward as we’re scrubbing out, the antimicrobial soap turning pink as it washes away invisible traces of the life we just helped save. “You’ve got hands like my grandmother.”

It’s meant as a high compliment. Her grandmother was a surgeon in Mumbai for forty years. I beam beneath my mask, my shoulders aching from holding retractors steady for hours, but my heart full.

“The patient’s pressure dropped twice, but you noticed even before the monitor alarm,” I reply, because in our world, this is how we say thank you.

As I exit through the hospital’s revolving doors at 8 PM, Manhattan hits me all at once—the cacophony of honking taxis, the smell of halal cart food mingling with designer perfume from passing women in business suits, the parade of humanity charging in every direction. The contrast between the sterile, controlled environment I’ve just left and this sensory explosion always takes a moment to process. In the OR, every movement is deliberate.

Out here, chaos reigns with its own strange order.

I stop at my favorite food cart on the corner of 168th and Broadway. Muhammad, the owner, starts preparing my usual before I even reach him.

“Ah, the surgical angel arrives!” he calls out. “How many lives did you save today?”

“I just assist, Muhammad,” I remind him, but I’m smiling. “The surgeons do the saving.”

He shakes his head while drizzling white sauce across my chicken over rice. “The surgeon is just the lead in the orchestra. Without you—” he gestures dramatically with his spatula, “—no symphony!”

I think of the patient today, a 62-year-old grandfather whose heart we repaired. How I monitored his vitals, counted sponges with meticulous care, anticipated complications before they arose, and kept the surgical field sterile and organized. How I maintained the chain of stability that allows surgeons to perform their miracles.

I take the warm container, inhaling the spices that remind me a little of my mother’s jollof rice, though I’d never tell her that. “Philosophy and flattery. That’s why you’re my favorite.”

“No, you come to me because I give extra sauce.” He winks, handing me the food. “Eat! You’re getting too skinny in that hospital. Nurses work too hard, take care of everyone except themselves.”

My apartment is a fifth-floor walkup with a view of other people’s apartments. The building is pre-war, which my landlord said like it was a feature rather than an admission that nothing has been properly updated since WWII. But it has character—crown moldings, hardwood floors that creak in specific spots I’ve learned to avoid when coming home late, and windows that catch surprising amounts of light at unexpected hours.

Tonight, I eat Muhammad’s chicken on my fire escape, watching the city transform below me. Washington Heights is its own microcosm of Manhattan—Dominican families chatting loudly on stoops, NYU medical students hunched over laptops in 24-hour cafes, longtime residents walking dogs and complaining about gentrification. The air smells like plantains frying and car exhaust and someone’s weed drifting up from the street below.

I check my phone and see a text from Zoey: “Drinks at Honey? New resident to initiate.”

Zoey is an ER nurse with an apparently inexhaustible supply of energy and a mission to introduce me to every bar between 14th Street and Harlem. I text back confirming while calculating how much sleep I can still get if I go out for “just one drink” (which never means just one). I should be exhausted—I spent four hours today as the scrub nurse in a complex spinal fusion, passing instruments, maintaining sterility, counting every needle and sponge—but there’s still adrenaline humming in my veins.

This is how we cope, I think. This is how we process the weight of holding people’s lives in our hands.

Honey is in the East Village, a dark, narrow space where the cocktails have ingredients I’ve never heard of and cost more than I should be spending. But tonight the hospital crew has commandeered a corner, and the loudest laugh belongs to Zoey, who waves me over.

“Finally! Our surgical goddess arrives!” She pulls me into the group. “Guys, this is O, the best hands in orthopedics according to Dr. Widmann, which means she’s basically royalty because that man never compliments anyone.”

I feel myself flush. “He only said that because I didn’t drop any instruments during that eight-hour spinal fusion last week and caught it in time when he almost used the wrong size implant.” The last part I say quietly, because there’s an unspoken code: we protect our surgeons’ reputations in public, even as we track their fallibility in private.

“And this,” Zoey continues dramatically, turning to a tall, uncomfortable-looking man clutching a beer, “is Dr. Daniel Chen, our newest trauma resident who needs to learn that in this city, sleep is optional and knowing your local bartender is essential.”

Daniel gives an awkward wave. His eyes are bloodshot, and I recognize the shell-shocked look of someone in their first month of residency.

“Welcome to hell,” I tell him with a grin. “The good news is, the coffee in the third-floor lounge is slightly less toxic than the stuff on five.”

“That’s your welcome wisdom?” Zoey scoffs. “Not the secret bathroom on nine that no one uses? Or the fact that Dr. Kaplan is only a monster before his 10 AM coffee?”

“Professional secrets,” I stage-whisper to Daniel. “You have to earn those. Like how to recognize a septic patient before the labs come back, or which anesthesiologists will actually listen to a nurse’s concerns.”

The night dissolves into hospital stories that would horrify civilians but have us crying with laughter—tales of lost objects in uncomfortable places, patients saying outrageous things under anesthesia, surgeons with superstitions so specific they border on magical thinking. I share the story of the cardiologist who insists on playing only Queen songs during procedures, claiming Freddie Mercury’s voice lowers patient blood pressure.

Later, as Zoey drags us to a second bar, then a third, the city shifts around us. Manhattan at night is a different creature than Manhattan by day. The buildings loom larger, their windows forming constellations more familiar to me now than the actual stars, which are mostly hidden by light pollution. We pass twenty-four-hour bodegas where cats guard towers of toilet paper, late-night pizza shops where a single slice bigger than my face costs less than the subway fare, streets that pulse with music from underground clubs.

“You’re quiet,” Daniel says as we wait for Zoey outside the bathroom of bar number three (or is it four?).

“Just observing,” I reply. “I still feel new here sometimes.”

“How long have you been in the city?”

“Three months. Feels like three years and three minutes simultaneously.”

He nods like this makes perfect sense. “I grew up in Queens, but Manhattan still feels foreign sometimes. Like it’s constantly reconstructing itself while you sleep.”

“Yes!” I exclaim, perhaps too enthusiastically. “I swear there was a bagel shop on my corner last week that’s now a vintage clothing store, and everyone acts like it’s been there forever.”

He laughs. “The Manhattan Mandela Effect. If you don’t take a picture, you can’t prove anything existed.”

“It’s like working in the OR,” I muse. “We transform chaos into order, then back to chaos, all in a matter of hours. A patient comes in broken, we fix them, they leave, and sometimes it’s like they were never there at all.” I pause, realizing I’ve veered into territory too philosophical for 2 AM. “Sorry. Occupational hazard—we either joke about everything or get existential.”

“No, I get it,” he says, serious now. “In trauma, everything can change in seconds. Like this city.”

The subway ride home at 2 AM is its own anthropological study. A woman in full evening wear sleeps upright next to a man in hospital scrubs (not ours). Teenagers take up an entire row, their energy undiminished by the hour. A street performer with a keyboard plays a haunting rendition of a pop song I can’t quite place. No one makes eye contact for too long—an unspoken rule I learned quickly.

I check my watch. Four hours until I need to be back at the hospital for pre-rounds. My feet ache in a way that suggests I’m still breaking in my body for this life—standing for surgeries, walking miles of hospital corridors, climbing to my fifth-floor apartment, dancing in bars with sticky floors.

As I climb the stairs to my apartment (elevator perpetually “coming soon”), I think about what my mother said about Manhattan eating me alive. Perhaps she wasn’t entirely wrong, but she missed the nuance. Manhattan doesn’t consume you completely—it takes little bites, tasting the parts of you that no longer serve while leaving the essential flavors intact.

I am still my father’s daughter, with his steady hands and analytical mind—traits that make me excellent in the OR, where emotions must be controlled and precision is everything. Still my mother’s child, with her stubborn resilience and secret softness—qualities that help me comfort families waiting for news and stay by a patient’s side when they’re afraid. But New York is reshaping me, surgery by surgery, street by street. I am becoming someone new against the backdrop of this ancient island—a palimpsest where every version of myself exists simultaneously.

Inside my apartment, I kick off my shoes and open the window. The city’s thrum enters—car horns, distant laughter, the clatter of the last late-night diners at the Dominican restaurant downstairs. I don’t set an alarm; my body knows when to wake by now, calibrated to the rhythms of the surgical floor. As I drift toward sleep, I imagine Manhattan breathing beneath me, its concrete lungs expanding and contracting, carrying millions of us through another day of ordinary miracles.

In the operating room tomorrow, I will hold retractors steady for hours while a neurosurgeon navigates the delicate landscape of someone’s brain. I will count instruments and sponges with the vigilance of someone who knows that a single missed item could mean another surgery, another risk. I will translate a surgeon’s terse commands into actions that could save a life. On the subway platform, I’ll sway alongside strangers each carrying their own invisible burdens. At the halal cart, Muhammad will call me an angel and give me extra sauce.

This is my New York symphony—surgical instruments clinking against metal trays, monitors beeping a patient’s vital rhythms, subway doors chiming their warnings, ice cubes tinkling in overpriced cocktails, and my own heart learning a new cadence in this city of perpetual reinvention.

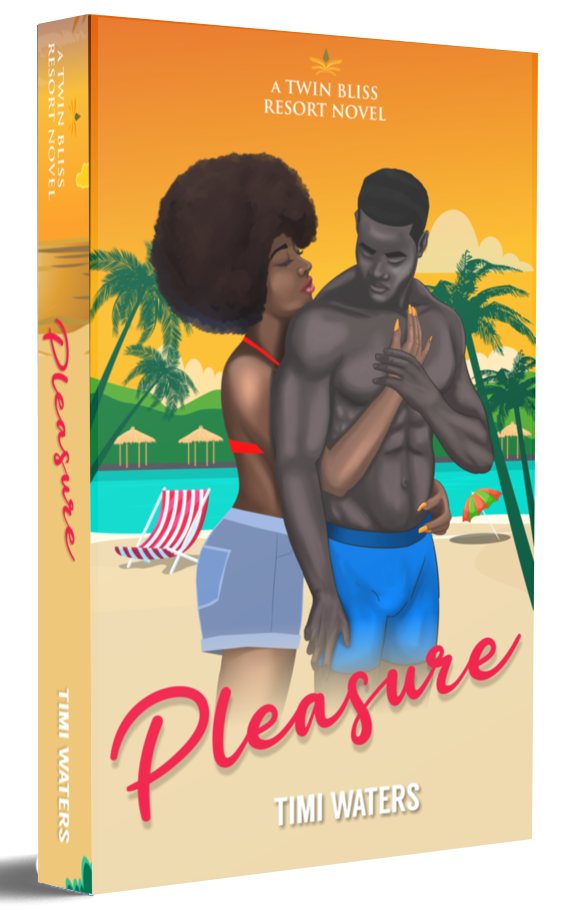

If you enjoyed this, you’d love Pleasure. Pleasure is a romantic thriller set in a holiday resort. Read it here.