There’s got to be a word for people like me. Biologically young bodies trapped in an old soul. I can’t stand rap music, metal rock, or the overhyped boy bands adored by girls my age. I listen, instead, to Nina Simone, Nat King Cole, and the Bee Gees.

My roommate, Zoe, thinks I’m ridiculous. She’s sprawled across her twin XL bed right now, scrolling through TikTok with the volume too high, while I’m trying to lose myself in Ella Fitzgerald’s “Misty.” The juxtaposition would be comical if it weren’t my daily reality.

“Ellie, you have got to come to Alpha Sig tonight,” Zoe says without looking up from her phone. “Jake said Tyler asked about you specifically.”

I pull one earbud out. “Tyler Johnston? The one who chugged an entire bottle of ranch dressing on a dare?”

“He’s pre-med!”

“Being pre-med doesn’t negate the ranch incident,” I counter, returning to my worn copy of The Great Gatsby. I’ve read it four times already, but Professor Harrington mentioned it in class yesterday, and I want his insights fresh in my mind for our next discussion.

Professor James Harrington. Even thinking his name sends a flutter through my chest.

“Earth to Eleanor!” Zoe waves her hand in front of my face. “You’re doing it again. That dreamy, far-off stare. Who are you thinking about this time? Humphrey Bogart?”

“He was before even my time,” I joke, but I feel heat rising to my cheeks. If she knew I was daydreaming about our History of American Literature professor, I’d never hear the end of it.

Ann Arbor in autumn is nothing short of magical. The University of Michigan campus transforms into a canvas of reds and golds, with the historic brick buildings starkly contrasting the vibrant foliage. I’m walking through the Diag, the crisp October air filling my lungs, on my way to meet my friends at Literati Café.

“Eleanor Price, are you seriously wearing a cardigan and loafers right now?” Marcus, my best friend since orientation week, calls out. He’s waiting outside the café with his boyfriend, Deon. “You look like my grandmother’s bridge partner.”

“Your grandmother must have impeccable taste,” I quip, giving them both quick hugs. “Besides, it’s practical. These Michigan winds are no joke.”

“She dresses like this because she thinks it’ll impress Professor Silver Fox,” Deon stage-whispers to Marcus. “As if he’ll suddenly notice her sophisticated style among the sea of U of M hoodies.”

“You told him?” I hiss at Marcus, mortified.

“Please, honey, he didn’t have to tell me,” Deon says, patting my arm. “The way you perk up like a meerkat whenever anyone mentions his name is subtle as a marching band.”

Inside the café, the scent of freshly ground coffee beans and old books provides an instant comfort. We settle at our usual corner table, and I can’t help but scan the room. Professor Harrington sometimes comes here on Saturdays to grade papers.

“You’re doing it again,” Marcus says, waving his hand in front of my face much like Zoe had done earlier. “Eleanor, he’s got to be at least forty.”

“Forty-three,” I correct automatically, then wince at their knowing looks. “It says so in his faculty bio.”

“Girl, you’ve got it bad,” Deon says, shaking his head. “What happened to that cute guy from your British Lit seminar? The one with the glasses and the beanie?”

“Noah? He asked me out for coffee, and I spent the entire time talking about the sociopolitical themes in Jane Austen’s work until his eyes glazed over.”

“On purpose?” Marcus asks.

I shrug. “He mentioned that he thought Pride and Prejudice was ‘kinda boring.’ It was never going to work.”

They both groan, and I can’t blame them. I know my crush on Professor Harrington is hopeless. Not just because of the age gap or the fact that he’s my professor, but because men like him—brilliant, passionate about literature, with salt-and-pepper hair and eyes that crinkle at the corners when he smiles—don’t look twice at awkward sophomore English majors who dress like they’re ready for a retirement community knitting circle.

Professor Harrington’s Tuesday afternoon lecture is the highlight of my week. I always arrive fifteen minutes early to secure a seat in the front row, which Zoe says is “peak nerd behavior,” but I can’t bring myself to care.

“So, Fitzgerald is showing us the corruption of the American Dream through Gatsby’s pursuit of Daisy,” Professor Harrington is saying, pacing in front of the whiteboard with an energy that belies his years. “But what’s often overlooked is how Gatsby’s reinvention of himself reflects the very essence of what makes the Dream so seductive—the idea that in America, you can become anyone you want to be.”

His passion for the material is infectious. While other professors drone on, reading directly from slides, Professor Harrington speaks as if he’s having an intimate conversation with each of us. When he gets particularly excited about a point, he runs his hand through his hair, leaving it charmingly disheveled.

“Any thoughts on this? Ms. Price, you look like you might have something to add.”

My heart stops. He knows my name. Of course, he does; I’ve contributed to discussions before, but hearing it in his rich baritone never fails to send a thrill through me.

“I, um,” I stammer, then take a deep breath. “I think there’s a tragic irony in how Gatsby succeeds in transforming himself externally—acquiring wealth and status—but fails to see that these things aren’t what truly matter to Daisy. He’s chasing a version of her that only exists in his memory.”

Professor Harrington’s eyes light up. “Excellent observation, Ms. Price. Gatsby’s fatal flaw is his inability to recognize that the past he’s trying to recreate is just that—past. He’s living in a fantasy, much like the fantasy of the American Dream itself.”

The approval in his voice makes me sit up straighter, a warm glow spreading through my chest. For the rest of the lecture, I’m floating, barely registering the envious glance from the girl next to me or the knowing smirk from my classmate Eddie, who has definitely picked up on my crush.

“I’m pathetic,” I announce to my friends as we sprawl across the floor of Marcus and Deon’s apartment that weekend. “I nearly had a heart attack because he remembered my name.”

“In fairness,” Marcus says, passing me another slice of pizza, “you do make yourself pretty memorable. You’re the only student who’s ever cited an obscure literary critique from 1978 during a class discussion.”

“It wasn’t obscure! It was a seminal work on—” I stop when I see them all exchanging looks. “Fine, I’m a cliché. The student with a crush on her professor. Tale as old as time.”

“If it makes you feel any better,” says Aminah, who joined our little group after we bonded over a shared love of vintage vinyl in our freshman dorm, “I saw him at the farmer’s market last weekend. He was buying kale. No one sexy buys kale.”

“Professor Harrington could make selecting produce look like a scene from a romance novel,” I sigh dramatically, flopping back onto a cushion.

“How do you know he’s not married?” Zoe asks, reaching for another beer.

“No ring,” Aminah and I say in unison, then high-five without looking at each other.

“According to Rate My Professor, he got divorced two years ago,” Deon adds, scrolling through his phone. We all stare at him. “What? I got curious. Oh, and apparently, he’s unfairly attractive for someone who assigns so much reading.”

“See? It’s not just me!” I exclaim, vindicated.

“El, honey, no one’s disputing his hotness,” Marcus says gently. “But maybe it’s time to channel this energy into someone more… attainable? Someone who won’t lose their job for dating you?”

I know they’re right. I’ve had this conversation with myself countless times. But every time I resolve to move on, Professor Harrington will say something brilliant about Hemingway’s use of silence, or he’ll recommend a book with such genuine enthusiasm that I can’t help but fall a little deeper.

The Michigan Theater is showing a restored print of Casablanca, and I’ve dragged Aminah along, promising her popcorn and the chance to appreciate Humphrey Bogart’s “smoldering intensity,” as she calls it.

“I still can’t believe you’ve never seen this,” I tell her as we find our seats. “It’s iconic.”

“Some of us were busy watching High School Musical during our formative years,” she retorts, settling in with her enormous bucket of popcorn.

The lights dim, and I’m immediately transported to Rick’s Café Américain. There’s something about black and white films that speaks to me—the glamour, the dialogue that crackles with wit, the way every shot is composed with such intention.

Just as Bogart delivers his first sardonic line, I spot a familiar profile several rows ahead. My heart performs an Olympic-level gymnastics routine. Professor Harrington is here, alone, his attention fixed on the screen.

“Oh, my god,” I whisper, gripping Aminah’s arm so tightly she winces.

“What? What’s happening?” she asks, alarmed.

“Three o’clock. Don’t be obvious!”

Of course, Aminah immediately whips her head in that direction. “Holy shit, it’s Professor Hottie! What are the chances?”

“In a town with one classic movie theater showing a film he literally referenced in class last week? Higher than you’d think,” I hiss, sinking lower in my seat. “Do you think he saw us?”

“No, he’s too engrossed in the film. Just like you usually are.” She pauses. “You know, this is actually perfect. You have something in common! Go talk to him after the movie.”

“And say what? ‘Fancy meeting you here, Professor Harrington. I, too, enjoy classic cinema and men who look like they stepped out of a J. Crew catalog circa 1992?’”

“I was thinking more along the lines of asking him what he thought of the restoration, but your way works too.”

Throughout the film, I’m hyperaware of his presence. I can’t focus on Ingrid Bergman’s luminous face or the tragic romance unfolding on screen. Instead, I’m wondering if Professor Harrington is enjoying the film, if he’s seen it before, if he’s the type to get emotional at the “We’ll always have Paris” line.

When the credits roll and the lights come up, Aminah nudges me. “Go. Now. Before he leaves.”

“I can’t just—”

“Eleanor Price, if you don’t take this perfectly orchestrated opportunity that the universe has handed you, I will never watch another black and white movie with you again.”

It’s an effective threat. Before I can talk myself out of it, I’m moving down the aisle, heart pounding in my ears. Professor Harrington is still seated, scrolling through his phone.

“Professor Harrington?” My voice comes out higher than intended.

He looks up, surprise registering on his face before recognition sets in. “Ms. Price. Eleanor, right?”

He knows my first name, too. This day should be marked in my personal history books.

“Yes, hi,” I manage. “I just wanted to say that I really enjoyed your lecture on Fitzgerald yesterday. Your point about the green light as a symbol of Gatsby’s idealized future really resonated with me.”

It’s not what I had planned to say, but it’s safer than commenting on the coincidence of our shared movie choice.

His face lights up with genuine pleasure. “That’s very kind of you to say. It’s always rewarding when students engage with the material so thoughtfully.” He glances at the now-empty screen. “Are you a fan of classic cinema?”

“Yes, huge fan,” I say, trying not to sound too eager. “I love the storytelling, the cinematography… there’s a certain magic to these old films.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” he says, and there’s a warmth in his smile that makes my knees weak. “They don’t make them like this anymore, do they?”

We fall into an easy conversation about favorite films and directors as we make our way out of the theater. Professor Harrington is surprisingly easy to talk to outside the classroom, listening attentively to my thoughts on Billy Wilder and offering insightful comparisons between Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon.

In the lobby, Aminah gives me a discreet thumbs-up from where she’s pretending to study the coming attractions poster.

“Well, I should let you get back to your friend,” Professor Harrington says, nodding toward Aminah. “But this was a pleasant surprise, Eleanor. It’s nice to meet a young person with such appreciation for the classics.”

“It was great talking with you too, Professor,” I say, trying to ignore the way my heart sinks at the “young person” comment—a stark reminder of the age gap between us.

“Please, outside of class, James is fine,” he says with a kind smile that doesn’t quite reach his eyes. There’s something there—a flicker of melancholy, perhaps—that makes me wonder what he’s thinking.

“James,” I repeat, testing the name. It feels intimate, forbidden.

He hesitates for a moment, then says, “There’s a film society that meets monthly at the community center. They show restored classics, followed by discussions. If you’re interested, their next screening is The Third Man. You might enjoy it.” He pulls out a business card and jots something on the back. “Here’s the information.”

I take the card, our fingers brushing momentarily. “Thank you. I’ll definitely check it out.”

As he walks away, I stare at the card in my hand, at his neat handwriting listing the date and time of the screening. It’s not a date. It’s not even close to a date. But it’s something—a small connection outside the classroom, a shared interest, a conversation that felt, for a brief moment, like we were just two people who love old movies, not professor and student.

“Well?” Aminah demands, hurrying over. “What happened? You were talking forever!”

I show her the card. “He invited me to a film society screening.”

Her eyes widen. “Eleanor! That’s huge!”

“It’s not what you think,” I say quickly. “He was just being nice. Professorial. Recommending an educational opportunity.”

“Uh-huh,” she says skeptically. “And I’m sure he gives all his students his personal business card with handwritten notes.”

I tuck the card carefully into my wallet, knowing I’ll analyze every aspect of this interaction for days to come. “Can we get ice cream? I need to process.”

The film society screening is in two weeks, and I’ve changed my mind about attending approximately seventeen times. On the one hand, it’s a public event. On the other hand, would my presence seem like I’m following him? Would it make him uncomfortable? Would it make ME uncomfortable?

“Just go,” Marcus says when I call him for the third time that week to debate the issue. “Worst case scenario, you watch a great film and avoid eye contact.”

So here I am, standing outside the community center in my most sophisticated outfit—a vintage-inspired dress that Aminah helped me select, paired with my grandmother’s pearl earrings—gathering the courage to go inside.

The screening room is already half full when I enter. I scan the crowd, not sure if I’m hoping to see Professor Harrington—James—or hoping he forgot all about it.

“Eleanor!” His voice comes from behind me. “You made it.”

I turn to find him smiling at me, looking different in dark jeans and a navy sweater instead of his usual blazer and button-down. Less like Professor Harrington, more like… James.

“I’m a sucker for Orson Welles,” I say, returning his smile. “How could I miss it?”

“Well, I’m glad you’re here. These discussions can get pretty lively.” He gestures to an empty seat near the back. “Shall we?”

My heart does a little flip at the “we,” but I remind myself not to read into it. He’s just being polite, making sure his student feels welcome in an unfamiliar setting.

The film is as brilliant as I remembered, full of shadows and moral ambiguity. I’m so absorbed that I almost forget Professor Harrington—James—is sitting next to me. Almost, but not quite. I’m hyperaware of his presence, of his occasional chuckle at a particularly clever line, of the way he leans forward during the famous Ferris wheel scene.

When the credits roll and the lights come up, the discussion begins. It’s fascinating to hear different perspectives on the film—some political, some focused on the cinematography, others on the performances. I listen, taking mental notes, working up the courage to contribute.

Finally, during a lull in the conversation, I raise my hand and offer my thoughts on the film’s exploration of friendship and betrayal. To my surprise, the group responds enthusiastically, building on my points. James catches my eye and gives me an approving nod that sends warmth spreading through my chest.

Afterward, as people gather in small groups to continue the discussion, he makes his way over to me.

“That was an excellent point about Holly Martins’ moral journey,” he says. “You have good insights, Eleanor.”

“Thank you,” I say, flushing with pleasure at the compliment. “This was fun. I’m glad I came.”

“So am I,” he says, and there’s a sincerity in his voice that makes my heart beat faster. “A few of us usually grab coffee after these screenings. Would you like to join?”

I hesitate, knowing that spending more time with him will only deepen my feelings, but I can’t bring myself to say no. “I’d love to.”

The coffee shop is cozy and dimly lit, with jazz playing softly in the background. I find myself in a small group with James and two other film society members—a retired English teacher named Margaret and a film student named David. The conversation flows easily, jumping from classic films to books to music.

“Wait, you like Nat King Cole?” James asks, surprised, when I mention my music preferences.

“And the Bee Gees,” I admit with a small laugh. “My friends think I was born in the wrong era.”

“I can relate,” he says, smiling. “My ex-wife used to say I was an old man trapped in a younger man’s body.”

Ex-wife. The confirmation of his divorced status sends a little thrill through me, even as I chide myself for it.

“I prefer to think of it as having timeless taste,” I say, and he laughs—a real laugh that transforms his face, making him look younger, more carefree.

It’s nearly midnight when we finally leave the coffee shop. Margaret and David head off in one direction, and James offers to walk me to my car.

“I’m actually just a few blocks away,” I tell him. “I walk everywhere in this part of town.”

“Then I’ll walk you home,” he says, as naturally as if we’ve known each other for years. “If that’s alright with you.”

It’s a clear night, the stars visible despite the city lights. We walk slowly, continuing our conversation from the coffee shop, discovering more shared interests and perspectives. He tells me about his dissertation on post-war American literature, and I share my dream of becoming an editor at a publishing house.

“You’d be excellent at that,” he says. “You have a keen eye for what makes writing work.”

“Is that your professional assessment, Professor?” I tease, feeling bold in the darkness.

He chuckles. “Yes, Ms. Price, that’s my professional assessment.” There’s a pause, and his voice takes on a more serious tone. “You know, it’s refreshing to meet a student who’s so genuinely passionate about literature. Many are just going through the motions, checking off requirements.”

Student. The word brings me crashing back to reality. That’s all I am to him—an unusually enthusiastic student.

We reach my apartment building too soon. “This is me,” I say, gesturing to the entrance.

“Thank you for coming tonight, Eleanor,” he says. “Your contribution to the discussion was valuable.”

“Thank you for telling me about it,” I reply, searching his face in the soft glow of the streetlight. There’s something there—a look, a moment of hesitation—that makes my breath catch.

But then he steps back, professional once more. “I’ll see you in class on Tuesday. Enjoy the rest of your weekend.”

“You too, Professor,” I say, deliberately using his title, reminding us both of the line that can’t be crossed.

As I watch him walk away, I’m struck by the contradiction of it all. I’ve never felt more seen, more understood by someone, yet I’ve also never been more aware of the gulf between us—age, position, circumstances. It’s bittersweet, this connection that can never be what I want it to be.

“So, it wasn’t a date, but it was kind of a date, but also definitely not a date?” Zoe tries to clarify as we’re getting ready for class the next week.

“Exactly,” I sigh, flipping through my closet for the fourth time. “And now I don’t know how to act around him in class.”

“Just be normal,” she advises, applying mascara with expert precision. “Which outfit are you overthinking right now?”

“The navy cardigan with the white blouse, or the burgundy sweater?”

She gives me a knowing look. “The sweater. It brings out your eyes.”

In class, Professor Harrington is his usual eloquent self, discussing Hemingway’s technique with passion and insight. If anything has changed, it’s subtle—perhaps he calls on me more often, or his eyes linger on mine a moment longer when I answer. But that could easily be my imagination, my hopeful heart seeing what it wants to see.

After class, as students file out, I linger, organizing my notes with deliberate slowness.

“Eleanor,” he says when the room has emptied. “Did you enjoy the film society event?”

“Very much,” I say, looking up at him. “I’m thinking of becoming a regular.”

He smiles, but there’s a guardedness to it that wasn’t there at the coffee shop. “They’d be lucky to have you. Your perspective is… refreshing.”

There’s an awkward pause, filled with things neither of us can say.

“Well, I should go,” I finally say, gathering my books. “I have a meeting with my advisor about next semester’s classes.”

He nods. “Of course. Take care, Eleanor.”

As I walk across the campus, the autumn leaves crunching beneath my feet, I wonder if this is how it will always be—this dance of approach and retreat, this connection that can never fully form. Part of me knows I should let go, focus on guys my own age, like the cute barista who always draws a little heart on my cup or Noah from British Lit, who still smiles at me despite the Austen incident.

But another part of me, the old soul that loves Nat King Cole and black and white movies, that finds beauty in the bittersweet and wisdom in longing, can’t help but cherish these moments of connection with someone who sees the world through eyes similar to mine. Even if nothing can ever come of it.

For now, I’ll continue attending film society screenings and participating enthusiastically in class discussions. I’ll savor our brief conversations and the shared glances that might mean nothing or everything. And maybe someday, years from now, when I’m no longer his student, when the gap between us seems less significant…

But that’s getting ahead of myself. For now, I’m nineteen going on forty-five, with an old soul and a young heart learning one of life’s hardest lessons: sometimes the deepest connections are the ones we can’t fully explore.

As Bogart said to Bergman, “We’ll always have Paris.” Or in my case, we’ll always have “The Third Man” and midnight conversations about Hemingway.

It’s not enough, but it’s something. And for now, it has to be.

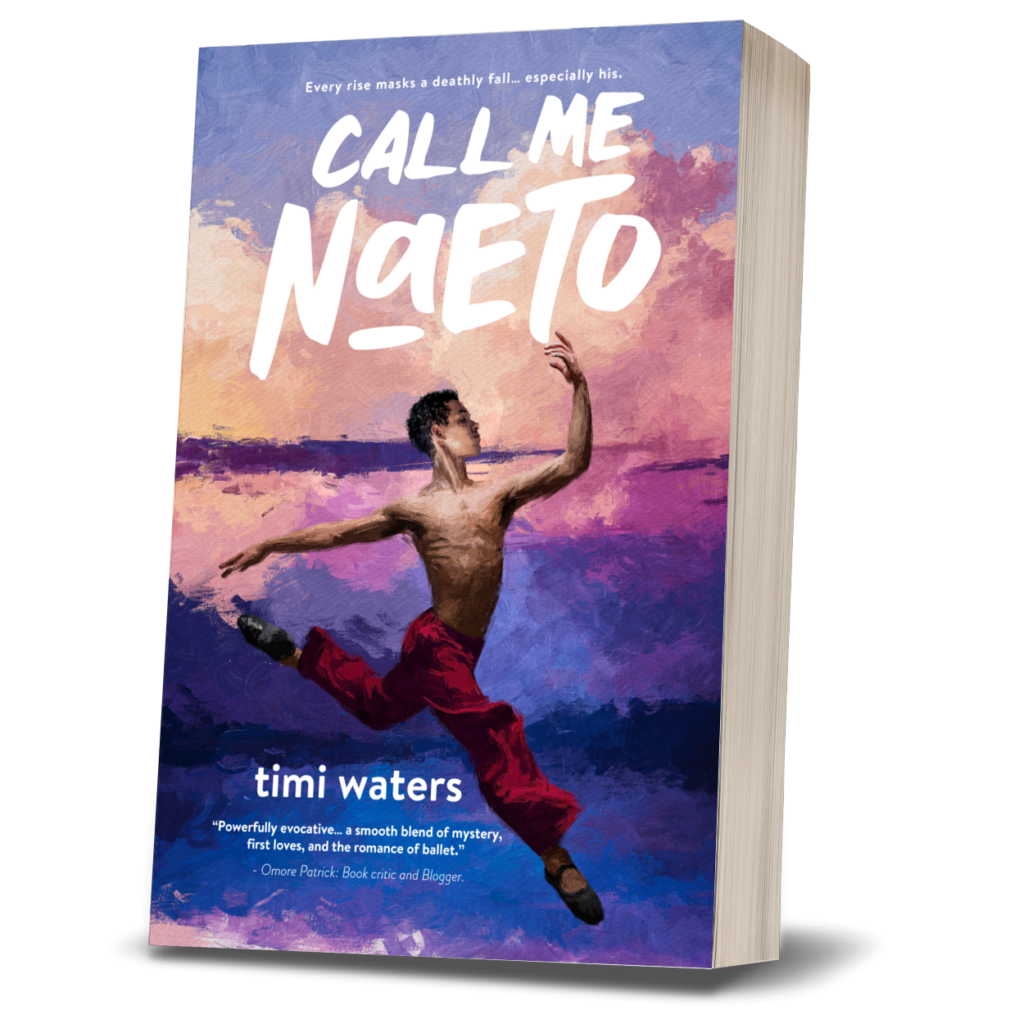

If you enjoyed this, you’d love Call Me Naeto. It’s young love in all its authentic intensity.

Timi Waters

Click HERE for buying options.